English to Norwegian: It is well known that English words occur in many contexts in Norwegian. We can roughly distinguish between two types of occurrences: words that denote things or phenomena for which there is no Norwegian word before, such as podcasting , smoothie or kiteboard , and words where there are already Norwegian alternatives, such as boots , support (support) and loser (loser).

The first category usually includes innovations, e.g. in culture and technology. In other words cases where language users use an English word for a cultural or subject-specific concept. Where the user do not have an established Norwegian conceptual apparatus to relate to.

The second category must be due to other factors. If in business, for example. chooses to advertise a position as project manager instead of project manager , the use of an English job title may be due to prestige considerations or a desire to appear as particularly internationally oriented.

In more general language use, English may reflect a desire to be linguistically innovative. To mark that you belong to a particular group. To show that you are hip and trendy, linguistically.

It is conceivable that young people’s frequent use of English words can be attributed to such sociological motivational factors. Although this group also uses many English import words that belong to the first category. The music genres house, dance , trash , metal, are a good example of this.

Lexicography

In linguistics and lexicography, the term Anglicism means an English import word. While neologism means a new word in the language. Word acquisition of English origin has a very long tradition in Norwegian, and many of the words are so ingrained that we rarely think of them as English. Think gang, kje ks and club .

In the research project Newer Anglicisms in Norwegian (NaNo), the goal is to account for import words of more recent date. Therefore these well-established Anglicisms are not addressed there. The work is based on the Norwegian newspaper corpus ( http: // avis.uib.no), which is collected at the Department of Culture, Language and Information Technology (Aksis) at the University of Bergen.

The newspaper corpus project builds up a very comprehensive text database. In turn a word database that forms a good starting point for studies of import words and Anglicisms. I want to show what occurs of newer English import words. With examples that are taken from the newspaper corpus. I will describe both word acquisition and the most common word formation processes that characterize English words in Norwegian-language contexts.

What kind of words are imported from English to Norwegian?

English to Norwegian. The use of English words is extensive, and it can be difficult to form a holistic picture of the collection of English words in this material and in Norwegian gen elt. A large part of the import words are taken from cultural areas. This is where the influence of Anglo-American culture is strong. Look at:

- Music ( heavy songs, indie artists, fusion jazz ).

- Sports ( floorball, kiteboard, semigreen ).

- Film / TV ( movie audition, location, gangster thriller, game show host ).

- Food / drink ( smoothie, bagel, fusion restaurant ).

Many import words represent subject terminology within a particular omadvice, Look at:

- Computer technology ( online, hardware, joystick mouse).

- Finance / business ( controller, hedge fund, lobbyist).

- Travel / tourism ( booking, sightseeing )

- Cosmetics ( foundation cream, lip gloss, fragr ance ).

But there are also very many import words that are not related to any particular academic or cultural area, but which simply represent general vocabulary. Consider baby boom, joine, kitsch, gadget, shortlisted, happening and shot glass .

Vocabulary

As the list suggests, the vocabulary is rich in nouns. But the other word classes are also represented, such as the devils funky, catchy and hip and the verbs chille, kite, maile, date and rule . It is also worth noting that English import words also include words and expressions that do not necessarily fit into the traditional word classes, but which in modern linguistic terminology are called discourse markers.

[1] Yess! Finally some damn fat Norwegian rap. [2] Random? Nope . Tom & Ed fix things from the start. [3] Natural, yeah right . Why do they have the little outfit [4] Get a life , only I say, says Kvitnes to VG.

The examples show that Yes ! (often spelled Yess !) can be used as an emphasizing (emphatic) expression that one is happy with something, while Nope has a more neutral value, and about the same function as Norwegian no . Yeah right is a not uncommon marker of irony. Whereas Get a life is an expression of (mild) frustration over someone’s actions or behavior. Such socially and attitudinally important expressions are called discourse markers or s amtaleparticles in modern linguistic terminology ( interjections in more traditionnational grammatical terminology), and the examples show that English is the source language for several such expressions.

Cap or caps , or shade hat ?

English to Norwegian: A characteristic of imported words is that they are usually subject to the same principles of inflection and article use as Norwegian words. To take nouns as imported an English tribe, which date , the tribe takes Norwegian inflectional, thus forming shapes like a date – date – several dating – all the data , s about all occurring in aviskorpuset. But there is also a great deal of variation when it comes to inflectional morphology. It is not uncommon for an English plural form to be imported in parallel with the English tribe

Example

[5] Police have made important findings at the scene, including a dark cap and several cigarette butts.

[6] Spears is said to have been wearing jeans and a cap during the ceremony.

[7] Nelson Mandela entered the stage, waved his cape and praised the city.

[8] At first Nils Johan Semb was so angry with Kjetil Rekdal that he threw his cap on the ground.

The examples show that two alternative forms, cap and caps , form the basis for Norwegian inflectional forms in the indefinite [11–12] and definite [13–14] singular forms. It can be called a cap – capen or a caps – capsen . In the process, the English s has thus lost its original majority meaning. But the plural form caps is also used with the plural meaning without a Norwegian ending, and thus there are three alternative forms in the indefinite plural form, such as respectively. examples [9], [10] and [11] show.

Example

[9] … an army of employees in similar company uniforms and funny caps .

[10] We gave away everything from caps to national team uniforms.

[11] Diesel shoes, Diesel watches, T-shirts and shorts, capes and hats, all with the Diesel brand on.

In the definite plural form, the form caps alone is not used.

Example

[12] The boys did not like to disguise themselves, but pulled the caps and hats well into their eyes.

[13] Thus, the World Cup organizers had to send a car to Gardermoen’s errand to pick up the capes that came by plane from Germany.

Competing Forms

There are other words competing forms – with and without the semantic set of redundant (redundant) plural s- one from English – in all parts of bøyningsmønsteret for such nouns. It seems that this type of morphological variation occurs primarily in single-syllable words ending in a consonant. Cap. Fan. Pin. Tight. Shot. Boot. To name a few. At the same time, there are a number of single-syllable nouns, such as babe and date, where the superfluous does not occur in the singular; so it can be called the babe but not the babe .

Another observation is that certain words have a strong tendency to take the suffix -ai particular form plural; both kids and kids occur, but the first form is by far the most common. Another interesting point when it comes to kid , is that the word only occurs in the majority in Norwegian.

Adjectives are also subject to a certain morphological variation. While ordinary Norwegian adjectives have an inflectional inflection with -t in the neuter and -e in a specific form or plural, this does not apply to English adjectives such as live or crazy .

It is thus called a towering crazy novel debut and the most crazy video recording I have been on. It was completely crazy conditions . The examples are in line with what is stated in Norwegian reference grammar. It is that English adjectives ending in -y do not have a conjugation inflection . But if we look at the adjectives trendy, sexy, corny, sporty and fancy in our material, we find that all have – e in the definite form and in the plural. Here, however, there is a lot of unploughed morphological ground. And indeed the NANo project aims to investigate the conditions for this variation.

Verbs

When it comes to imported verbs such as rule. It is most common that they follow the inflectional pattern of the English to Norwegian verb kaste. It is thus called It was in the seventies Steely Dan ruled in the past tense, and then they had ruled the whole world in the effect. But that there is variation here too. Take the example This song rolled when it came. The forms with – a also occur. In the 80’s it was pink as rula.

It is currently too early to draw clear conclusions about morphological inflection patterns, but the project aims to study them in detail. The Norwegian newspaper corpus contains dated material from every single day over a ten-year period, and this enables us to study this development over time and thus follow e.g. the battle between cap and caps on direct, so to speak. So far it turns out that the s -forms make up approx. 80–90 per cent of the use (of the caps / cap alternatives ), and that this figure is fairly stable over the entire ten-year period that the material represents.

Ordnance processes

It is common to import words from English to Norwegian, and they also form the basis material for new Norwegian words in various word formation processes. The most common form of new word formation is composition, ie that a new word is composed of one of independent words. English-based compositions can be imported in their entirety, such as acid jazz or heavy rock , or they can consist of one or more English composition elements , such as the acid jazz wave , babe factor or east edge playboy .

Conversion is another fairly common word formation process where anglicisms are included, and means that a word stem is used in a new word class without the addition of derivation morphemes. Common examples of this are the formation of verbs from nouns, such as chat —> to chat, mail —> to email , and even on the basis of names, as in Google —> to google . Furthermore, such verbs can in turn form the basis of nouns, such as chatting —> a chatter (person chatting).

Derivation is a third form of new word formation and consists of a word being used in a new word class by means of derivation morphemes, e.g. the suffixes -skap, -het and – else . Derivation seems to be far less common than composition and conversion in our material, but some examples exist, such as cool —> coolness and the obviously productive – like , as in fictional .

Norwegianization

English to Norwegian. Some new words are Norwegianized, ie the original spelling doesn’t transition over well from English to Norwegian pronuniation, and so they get a spelling that corresponds better with Norwegian pronunciation rules than with the original English spelling, as a guide for guide and south for service . The Language Council has adopted a number of Norwegianised spellings as alternatives to the still permitted English spellings.

It is in line with the Norwegian language policy tradition that there should be good correspondence between writing and speech. It can of course take some time before Norwegianized forms gain a foothold, and in the material we have examined, it is still much more common to use the English version of both guide and service..

But at the same time, the Norwegianized forms outcompete with worde from English to Norwegian such as hip ( hip ) and streit ( straight ). However, it is important to note that we have only studied the newspaper language, and here the spelling will be influenced by the newspapers’ internal regulations on language use. It is also conceivable that Norwegianisation has gained a better foothold in other areas where the written language is used.

Standardization

The term Norwegianisation is most often used in connection with the Language Council’s standardization cases. However Norwegianisation also occurs as an independent process in that language users themselves use a new spelling for imported words. The material shows that the adjective døll is most often Norwegianized, and dull is written less often . The forms døll / dølt, øgli, kreisi and jønk are all examples of Norwegianisations that are not among the spellings that the Language Council has proposed. In other words, there is a not insignificant motivation for this orthographic adaptation among the language users themselves.

In the language of the newspaper, Norwegianisations also tend to occur in multilingual contexts, where proposed norms are discussed; cf. I also think that beiken and køp look strange . It is also worth noting that partial Norwegianisation can occur, as in jønkfood , which is composed of a Norwegianized and a non-Norwegianized component.

Are Norwegian alternatives an alternative?

The use of words from English to Norwegian can provoke reactions from many, and it will often be desirable to try to find Norwegian alternatives to the imported word in the form of a replacement word.

There are many examples of good replacement words, such as whiplash instead of whiplash. It is clear that choosing English words where there are clear Norwegian alternatives, can often seem ill-considered. When business chooses to talk about controller instead of accounting manager. It may seem both unnecessary and pretentious. There is every reason to recommend Norwegianisation. Furthermore, there are good reasons to promote the use of Norwegian terminology in subject areas that are at risk of suffering domain loss, something the Norwegian Language Council’s report Norwegian in a Hundred! (Språkrådet, 2005) strongly emphasizes.

This is the most important measure to ensure that it is possible to communicate and teach in Norwegian in all subject areas.

But a point that must not be overlooked in this context is that it is not always unproblematic to replace Anglicisms with a Norwegian alternative. When it comes to the general vocabulary, there are cases where English to Norwegian replacement words will not necessarily be the best solution.

Example

[22] E dokkar døll , or, resounds from the stage.

[23] You are good and pretty, you’ll join Deiter ?

[24] Do not wear boots and a clean-shaven head.

The examples illustrate three very common, newer Englsih to Norwegian Anglicisms in, døll, deit and b + oots. The reasons why perhaps especially younger language users choose these words are many and complex. It is conceivable that possible Norwegian avløserord could have been respectively kjedel yesterday , rendezvous or boots. But if these alternatives will have some impact among language users, is uncertain. Furthermore, it is not necessarily the case that boring in all cases means the same as dolly. Or that young people who date are preoccupied with the same thing as was previously done at dates. And it is very conceivable that bootsv in fact represents a special type of boots, and that the imported option is therefore not easily replaceable.

English to Norwegian Anglicisms can often represent linguistic nuances that the Norwegian alternative does not cover. As a result their use can actually be a lexical enrichment. We now have the options dull and boring, which do not mean the same thing, but which exist side by side and represent linguistic nuances. It also seems unfruitful to try to promote the use of Norwegian alternatives to some cultural concepts, such as the music forms house , dance and trash . Here it seems to be better to keep the original, as we have a tradition of using blues , rock and jazz. Therefore, it is not certain that Norwegianisation is always possible or desirable from a holistic communicative and cultural perspective.

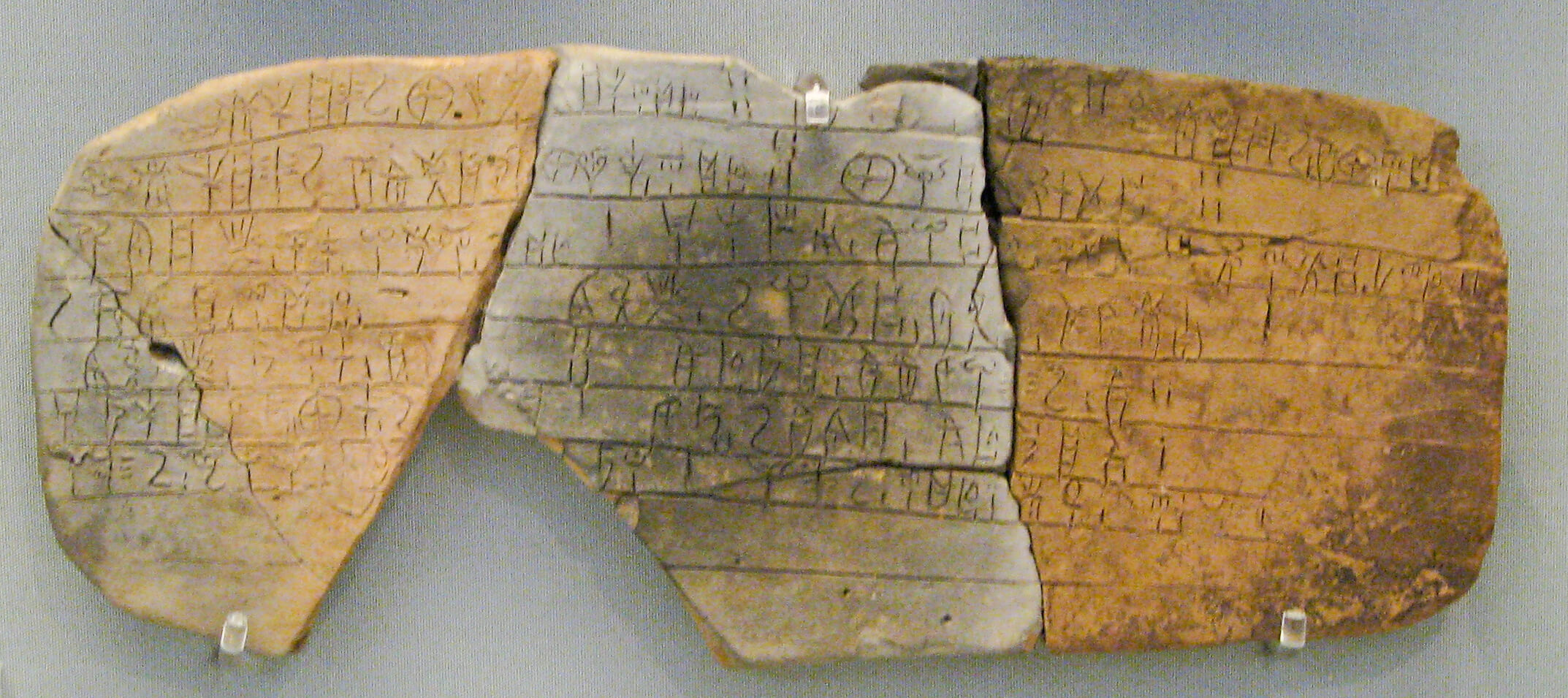

English to Norwegian language history

Around the year 600, the language in the runic inscriptions shows a transition to a newer language form. This is because the old stem vowels began to fall away (the syncope period). The language of Eggjasteinen , supposedly from almost the year 700, has several words without these vowels, such as fiskR, stain and the participle form skorin, instead of the Old Norse forms fiskaR, stainaR and skorinaR . Along with the loss of vowels, different kinds of sound and refraction penetrated and gave the language a different character than before.

From Old Norse to modern Norwegian

The Norwegian language belongs to the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. But the language of the first people who settled in this country after the last ice age, was probably quite different from the language we speak today.

Norwegian has much in common with other Nordic languages. If we go back a thousand years in time, there was the greatest similarity between the Norwegian, Faroese and Icelandic languages. Today, Norwegian has more in common with Danish and Swedish.

Before 1814, Norway was strongly influenced by Denmark and the Danish language. During the long union period with Denmark, the Bible, the book of Psalms and the catechism were only published in Danish. The printing presses were located in Denmark and all books and reading material were printed in Danish. When Christian IV’s Norwegian law came in 1604, it was also written in Danish.

In 1814, Norway got its own constitution, its own parliament and Storting, but now entered a period under Sweden. Even Danish was the written language. Danish dialect with a Norwegian accent was common for officials and the upper class.

Improve your english vocabulary while fine-tuning your dSLR front/back focus

Nevertheless, the majority of the Norwegian population spoke some form of dialect. The debate about one’s own Norwegian language began in the early 1930s. The language debate became a great controversy, some wanted to keep the Danish written language, while others wanted to Norwegianize Danish a little. Henrik Wergeland was among those who wanted to Norwegianize Danish. He used Norwegian words like barn and boy in place of the Danish words kostald and boy. Asbjørnsen and Moe wrote in Danish with some special Norwegian words. The historian PA Munch was one of those who wanted to create a Norwegian written language based on a dialect.

Ivar Aasen – “The father of Nynorsk” – English to Norwegian

Aasen traveled around Norway and collected words and grammar forms from the dialects. The intention was to use the collected material to develop a Norwegian written language that should be as common as possible and be as close to Old Norse dom as possible. The collection work resulted in “Det norske Folkesprogs Grammatikk” (1848), “Ordbog over det norske Folkesprog” (1850) and “Prøver af Landsmaalet i Norge” (1853). Aasen wanted to weed out many of the German loanwords, and did not want to use so many foreign words. It would be just a valid form of a quarter of a word, there would be no optional forms.

Knud Knudsen – “The father of Bokmål” – English to Norwegian

Knudsen worked all his life on the continuation of Wergeland and Hielm’s thoughts of gradually Norwegianizing Danish, similar to the transition from English to Norwegian. He wanted the written language to reflect the spoken language as best he could. By speech, Knudsen means the daily speech. He also went in to replace a number of prepositions with “real” Norwegian words. Some of Knudsen’s ideas and proposals were implemented as early as 1862. For example, dumb e was abolished, double vowel was abolished and ph became f. The official name of the Danish-Norwegian written language became national language (from 1929 it is called Bokmål) to use hard consonants where Danish uses blue consonants.

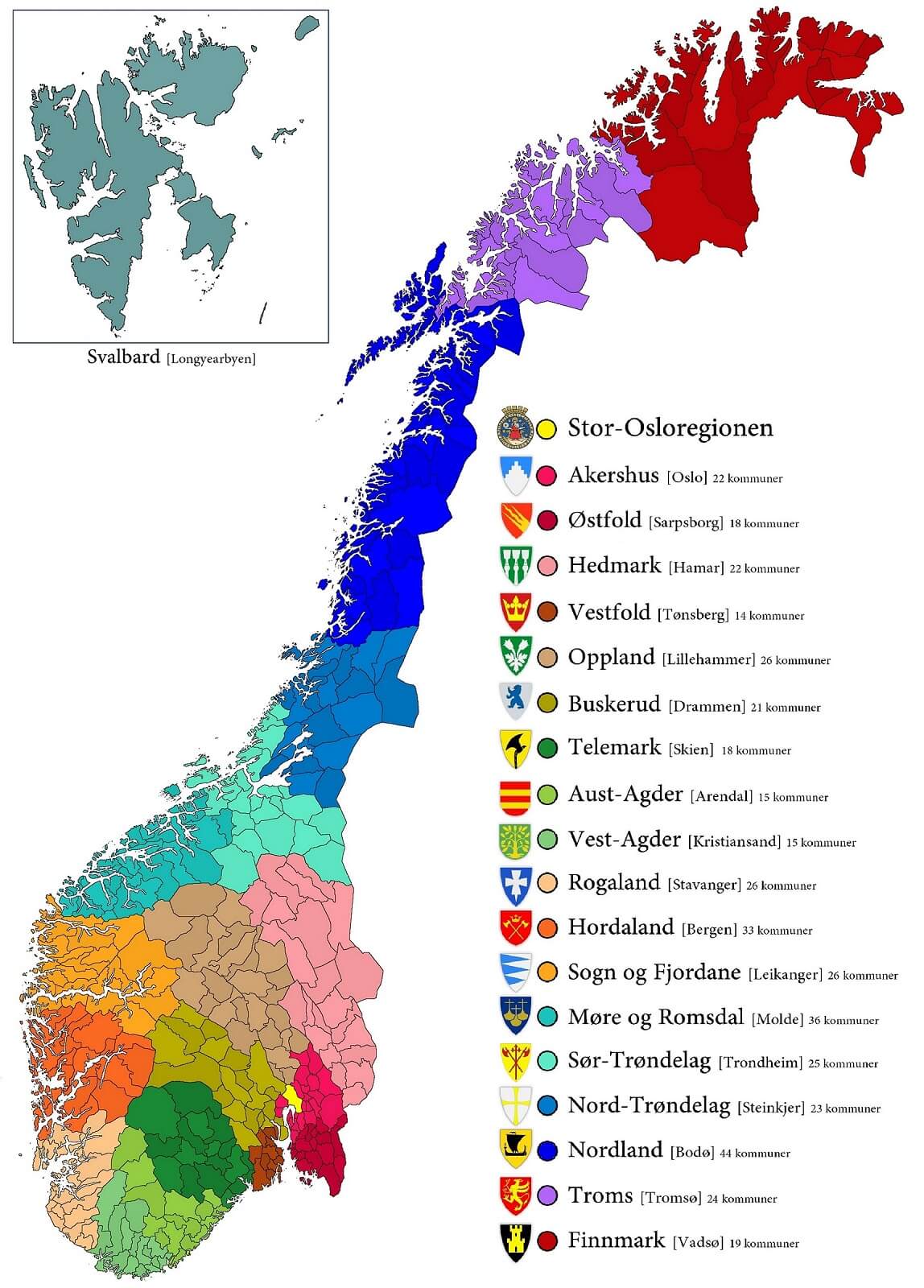

The goal struggle came into Norwegian politics in earnest in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1874, Ole Anton Quam proposed that national language and Old Norse should be included as subjects in the teacher training colleges, but the proposal was voted down. In 1885, the equality decision was adopted, which means that national languages and national languages should be equal in the school and in public administration

1892

By the time of 1892, it was decided that the school board in the various municipalities should decide whether the pupils should have teaching and books in national or national languages.

The same year there was a new reading book for the folk school, which was made by Nordahl Rolfsen. Rolfsen made the language more national and accessible to school children and followed many of Knudsen’s thoughts. A problem arose, it was not the intention for the students to use all the forms they found. This naturally led to some errors in the written work of the students. At the same time, the ministry introduced a new spelling of some words and optional forms, without informing the schools well enough. These optional forms created uncertainty among school students.

1905

In 1905, Norway leaves the union with Sweden, and after a referendum, the country becomes a kingdom. Riksmål and Landsmål were the two official languages in Norway in 1905. The Riksmål differed little from Danish, and Norwegianisation had to continue. Knud Knudsen died in 1895, and it was Molkte Moe, son of Jørgen Moe, who took up the inheritance after him.

His main argument for a greater Norwegianization of the written language was that Danish spelling was an obstacle to Norwegian popular education. After a quarter of an hour, those who wanted to keep the Danish written language also switched to the Norwegianisation line, one of the reasons for this was due to the strong progress for the national language. In 1907, everyone who took the artium exam had to write two Norwegian styles. One in national language and one in national language. In 1909, over 1,300 school districts used national languages.

Industrialization to centralization

In the first decades of the 20th century, a new Norwegian society emerged. Industrialization led to a centralization, and especially to the cities in Austland. The working class grew, and they gained political influence and power both in the municipalities and in the Storting. In the long run, population and political changes led to changes in the preconditions for the written language.

In 1907 came the language reform that marked a clear break with Danish-Norwegian. The blue consonants (b, d, g) were replaced with hard consonants (p, t, k). This reform took effect immediately. The schools used it, and books were printed after the new spelling. Knud Knudsen’s Norwegian ideas had come a long way, and won ten great victories.

1917

In 1917 continued the work of bringing the Danish-Norwegian national language closer to the Norwegian spoken language. The national language also underwent a change in that more attention was paid to Australian dialect forms. The main point of the reform was the idea that national languages and national languages should be merged sometime in the future, so that Norway got a written language.

The reform of 1917 met with great opposition, especially conservative forces thought that the new optional forms that had been introduced were too radical. Molkte Moe continued to work with this idea and introduced the concept of “common Norwegian” about the two merged forms of Norwegian. In the 1920s, many municipalities and counties got new names. For example, Kristiania became Oslo, Steinkjær became Steinkjer and Bratsberg became Telemark. In 1917, there was a large replacement of æ to e. Therefore, there was a change in, for example, Steinkjær to Steinkjer.

1929

In 1929, national languages and national languages were replaced with Bokmål and Nynorsk. The 1938 reform was very comprehensive. The idea behind the reform was to make spelling easier, but the opposite happened. Even more optional forms were introduced to carry forward the approach of Nynorsk and Bokmål. There was considerably greater use of diphthongs and it became mandatory – a ending in a specific form singular gender. The reform aroused great opposition among Bokmål people. They fought for the book language not to be influenced by the idea of approach and New Norwegian.

Rebuild

After World War II and the five-year German occupation, countries must be rebuilt. Norway is a developing country, and in the years to come, oil was found in the North Sea, which led to large revenues for the country. The traditional home-grown woman applies for educational opportunities and work. Norway is becoming more and more dependent on the international economy, both in ups and downs. At the same time, things happen with language. Riksmålsforbundet launched an action against the language in the textbooks in 1951.

The parents of many school children in the largest cities hadd issue with this. Primiarily on the western edge of Oslo, they did not want to find themselves learning the other “languages”, or comparing English to Norwegian that filled the textbooks. It all developed into one of the most dramatic language battles we have had in Norway. A signature campaign was launched, and it quickly spread throughout the country. The committed parents managed to collect about 400,000 signatures against the common Norwegian in the textbooks.

In 1952, the Norwegian Language Board was established. The tribunal’s task was to continue the work of promoting the approach between Bokmål and Nynorsk. Opponents of the common Norwegian, especially the Bokmål people, raged against this. In 1954, parents in the Oslo area began to direct the ABC books to their children. Some words were erased, and corrected with pen and ink. This is how some people read the hen and the cow, while others read the hen and the cow. The strong reactions to the authorities’ language policy resulted in a change of course. The Norwegian Language Board prepared a new textbook standard in 1959. It determined which forms were to be used in textbooks. Several of the approaches in Bokmål were removed.

Language development – English to Norwegian

English to Norwegian: Language history in Norway is the story of how the Norwegian language has developed from the first inhabitants settled in this country until today.

Language changes can be divided into two types:

- Changes in the language itself. Such changes primarily affect the sound and design. For example, certain sound combinations change more easily than others. The sound combination skj was in Norse times pronounced as three separate sounds, but is pronounced in modern Norwegian as one: sj. Within the former, we see that more and more words have a slight inflection. Such changes are usually unconscious, noticeable difference from English to Norwegian.

- Changes as a result of societal development. Also conditions outside the language, e.g. political decisions, relocation and contact between language users, cause the language to change. Such changes primarily affect the vocabulary. This type of change can be both planned and unconscious.

The future of the Norwegian language – English to Norwegian

There is a fear that now that English is such an international language, Norwegian will gradually disappear. Loan words are becoming more common and Norwegianisation is being looked down upon more.

Several universities have English as the language of instruction, as there are more textbooks and resources available in English rather than Norwegian. It is also more common for bachelor theses and other major assignments to be written in English.

We also have more access to English-speaking media, and not just through the Internet. Most TV series and movies in cinemas are in English with Norwegian subtitles. Very few songs played on the radio are Norwegian, even the songs released by Norwegian artists! There is therefore very little Norwegian-speaking content and this makes it more natural for us to hear English. We are surrounded by a language that is not our own.

Language Council

The Language Council was established in 2005 as a body focusing on strengthening and protecting the Norwegian language. The Language Council engages in Norwegianization and Norwegianisation of foreign words. This leads to changes such as “chauffeur” becoming “driver”. Even suggesting “service” can be written as “southern” .

The Language Council has a whole list of replacement words . It is important to note that in several of these words the English term is more commonly used, such as “cottage cheese” which is used more often than the replacement word “cottage cheese”.

Even with the Language Council trying to strengthen the Norwegian language, the internet brings with it many new loanwords that come and go. Far too fast for us to get a Norwegianization of them. Due to developments in transport and globalization, more people are moving to Norway with Norwegian as their second, if not third, language. This may lead us to end up using English in public and Norwegian at home. As such English is more used in professional situations nowadays and can make it easier in a multicultural society.

English to Norwegian

Much of Norway’s history and culture lies in the language, as in most languages, and this makes it important to preserve our written languages. You can easily do this by reading more books and articles in Norwegian. Or even better if you read what is written by someone with good writing skills. You may want to check out authors such as Lars Saabye Christensen, Jo Nesbø and Anne B. Ragde. They are all Norwegian authors with good experience in writing.

If you get used to reading Norwegian written correctly, it is easier to improve your writing skills. Reading and writing go hand in hand.